Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines

Systematic Reviews and Clinical Practice Guidelines 2.0

GED Guidelines 2.0 Methodology

Methodology: The Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines 2.0 A Model for Developing Subspecialty Clinical Practice Guidelines: The Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines 2.0 Satheesh Gunaga DO, Christopher R. Carpenter MD, MSc, Maura Kennedy MD, MPH, Lauren T. Southerland MD, MPH, Alexander X....

Read MoreSystematic Review: Falls

Systematic Review: Fall Prevention Physical and Occupational Therapist Evaluations for Fall Prevention in the Emergency Department: A Geriatric ED Guidelines 2.0 Systematic Review A systematic review Lauren T. Southerland, Pedro K. Curiati, Richard D. Shih, Alexander X. Lo, Kristie Harper,...

Read MoreSystematic Review: Dementia | Pain Management

Systematic Review: Dementia | Pain Management A Systematic Review Evaluating Pain Assessment Strategies for Patients With Dementia in the Emergency Department: The Geriatric ED Guidelines 2.0 A systematic review Sangil Lee, Alexander X. Lo, Teresita M. Hogan, James D. van...

Read MoreClinical Practice Guideline: Delirium

Clinical Practice Guideline 2.0: Delirium GRADE-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines for Emergency Department Delirium Risk Stratification, Screening, and Brain Imaging in Older Patients With Suspected Delirium A practice guideline Sangil Lee, Danya Khoujah, Debra Eagles, Maura Kennedy, Alexander X Lo, Christian...

Read MoreSystematic Review: Delirium | Detection

Systematic Review: Delirium | Detection Delirium detection in the emergency department: A diagnostic accuracy meta-analysis of history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and screening instruments A systematic review Christopher R. Carpenter MD, MSc, Sangil Lee MD, MS, Maura Kennedy MD, MPH,...

Read MoreSystematic Review: Delirium | Head CT Findings (2 of 2)

Systematic Review: Delirium Delirium, confusion, or altered mental status as a risk for abnormal head CT in older adults in the emergency department: A systematic review and meta-analysis A systematic review Sangil Lee, Faithe R Cavalier, Jane M Hayes, Michelle...

Read MoreSystematic Review: Medications | Severe Agitation

Systematic Review: Medication Comparative Safety of Medications for Severe Agitation A Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines 2.0 Systematic Review Martin F. Casey, MD, MPH; Natalie M. Elder, MD; Alexander Fenn, MD; et al J Am Geriatr Soc | Epub | April...

Read MoreSystematic Review: Delirium | Risk Stratification

Systematic Review: Delirium Risk factors and risk stratification approaches for delirium screening: A Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines 2.0 systematic review Justine Seidenfeld MD, MHS, Sangil Lee MD, MS, Luna Ragsdale MD, MPH, Christian H. Nickel MD, Shan W. Liu MD,...

Read MoreSystematic Review: Palliative Care

Systematic Review: Palliative Care Emergency department-initiated palliative care screening among older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol Dimitri E Lin, Satheesh Gunaga, Fabrice I Mowbray, Eric D Isaacs, Daniel Markwalter, Naomi George, Alison E Hay, Rita Manfredi, Erica Westlake,...

Read MoreGED Guidelines 2.0 Meeting: October 2025

Supported by the American Geriatrics Society, the John A. Hartford Foundation, and NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

Brief History of Geriatric Emergency Department (GED) Guidelines:

Lowell Gerson published one of the earliest manuscripts exploring the future impact of an aging America on the fledgling specialty of emergency medicine in 1982. Nearly a decade later, the John A. Hartford Foundation provided a grant that catalyzed formation of a Geriatric Task Force at the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, a series of original research manuscripts in Annals of Emergency Medicine (Lowenstein 1986, Skiendzielewski 1986, Jones 1986), and a 1996 textbook edited by Art Sanders entitled “Emergency Care of the Elder Person” (Figure below from Hogan 2023). Around the country, early thought leaders like Larry Lewis and Doug Miller began to explore the ramifications of aging physiology with cognition and gait on general emergency department operational flow and diagnostic efficiency. Ula Hwang's paper "The geriatric emergency department" provides insight on structural and process of care modifications to address the special needs of older patients (http://pmid.us/17916122). Tess Hogan's 2023 paper explains the progress early Geriatric Emergency Medicine advocates have made to deliver adequate care for the aging population (https://institutionalrepository.aah.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1044&context=jgem).

In November 2008 Holy Cross Hospital Silver Springs Maryland opened the first self-identified GED in response to the poor care received by his own mother during an ED visit. EM physicians and nurses were trained in GEM, and a full-time geriatric social worker guided older patients’ care. The second GED opened under the leadership of Mark Rosenberg, at St. Joseph’s Hospital in Patterson New Jersey in April 2009. Patients were happy with the care, and favorable press releases increased older adult volumes. This led to the formation of a 20- bed GED continuous with the main ED. Soon geriatric protocols were applied to all older adults in the entire ED, and specialized staff moved to each bedside as needed. Guided by these successes, all manner of hospitals began to self-identify and market their EDs using terminology including silver emergency room, senior ED, geriatric-friendly ED, and others. These so-called senior EDs featured improvements that ranged from a box containing a hearing aid and reader glasses to an entire ED staffed with physical therapists, social workers, and geriatric-trained ED nurses.

Recognizing the heterogeneity of quality and emergency care experience across emerging self-described “senior EDs” the American College of Emergency Physician’s (ACEP) Geriatric Section and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) Geriatric Emergency Medicine Interest Group (now Academy of Geriatric Emergency Medicine), convened a team of emergency physicians, nurses, and geriatricians in 2011 to create a more standardized approach to age-friendly emergency care. Consequently, in 2014, the GED Guidelines (GEDG) provided recommendations for institutions and departments seeking to establish geriatric emergency care improvements. The GEDG list 33 recommendations identifying best practices in older adult emergency care and were endorsed by the Board of Directors of SAEM, ACEP, American Geriatrics Society, and the Emergency Nurses Association in 2014 as well as the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians, American Academy of Emergency Medicine, and American College of Osteopathic Emergency Physicians in the years that followed.

The GEDG recommendations were foundational for increasing the recognition of the unique needs of aging adults during times of emergency to a wider audience. The GEDG served to identify a group of best practices and corresponding quality metrics in emergency older adult care. This listing catalyzed and enabled care improvements throughout the country, resulted in enhanced older adult care service lines at hospitals nationwide, and enabled the formation of the Geriatric Emergency Department Collaborative (GEDC, see https://gedcollaborative.com/). GEDC innovators then developed the concept of a Geriatric Emergency Department Boot Camp (http://tinyurl.com/GeriBootCamp2015ACEPNow) to help individual hospital systems implement transdisciplinary and measurable geriatric care improvements in their EDs. The goal was to promote the dissemination and implementation of the GEDG by linking actionable guideline recommendations with individual hospital’s ongoing quality improvement efforts. The work funded by John A Hartford Foundation and the Mary and Gary West Foundation, served to ignite emergency older adult care improvements in initially dozens and eventually hundreds of EDs.

In 2017, ACEP recognized the need to help regulate the confusing claims of improved older adult care for the public. In May 2018, ACEP launched The Geriatric Emergency Department Accreditation Program (GEDA, see https://www.acep.org/geda). GEDA provided explicit criteria to attain three tiers of accreditation and designated reviewers to confirm adherence to those criteria, mirroring the more familiar trauma center designations (http://www.acepnow.com/article/acep-accredits-geriatric-emergency-care-emergency-departments/). The first ACEP accredited GED was Ascension Columbia St Mary’s Hospital Ozaukee approved on November 5, 2018. ACEP has accredited over 500 GEDs worldwide by mid-2024 (http://tinyurl.com/GlobalGeriED2016 and https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20170912.061810/full/).

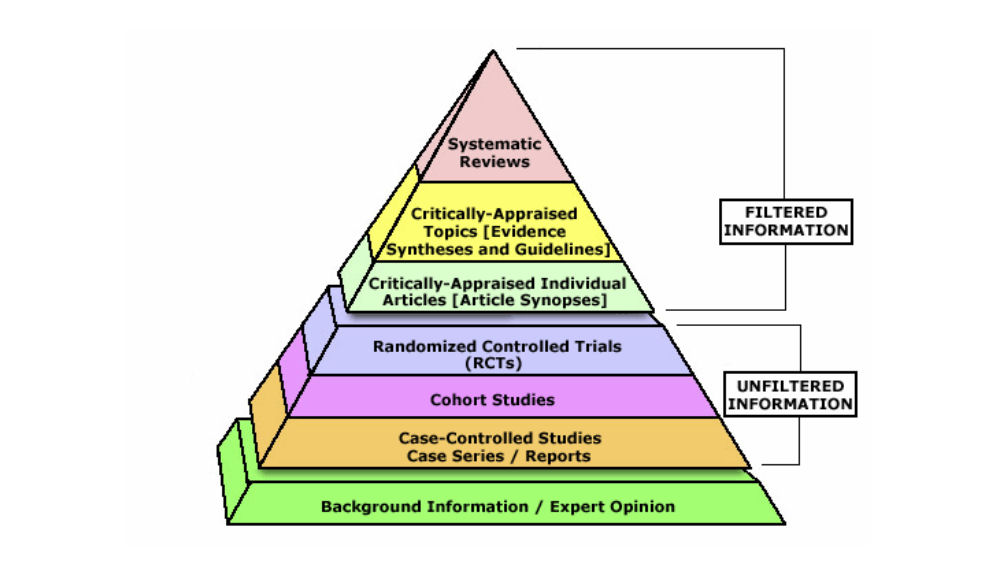

Evidence Based Medicine Hierarchy of Information

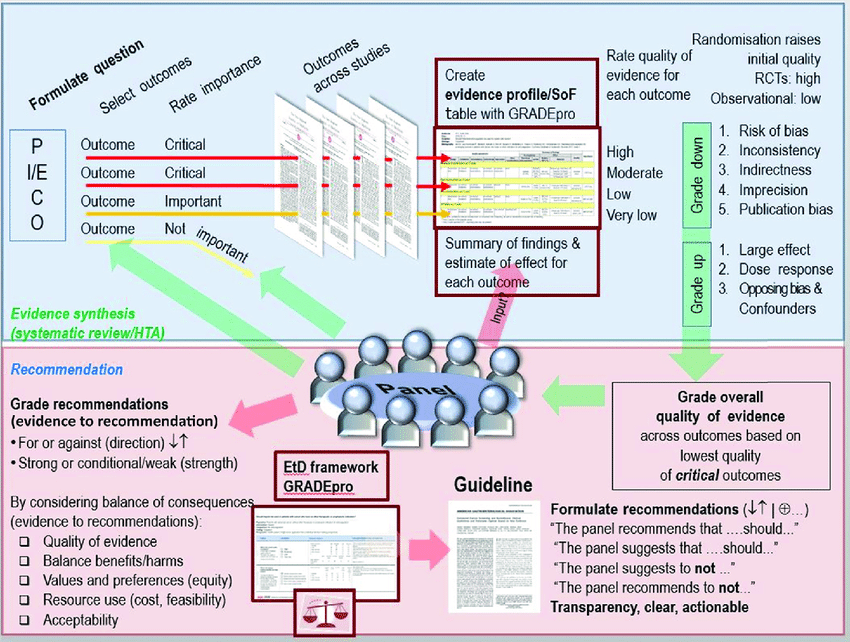

Clinical Practice Guidelines are graded based on the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations, often using systems like the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) approach. These systems determine how strongly a guideline should be recommended based on the certainty of the evidence supporting it. GRADE is used by 110 organizations worldwide that create Clinical Practice Guidelines. This is the technique deployed to update the 2014 GED Guidelines.